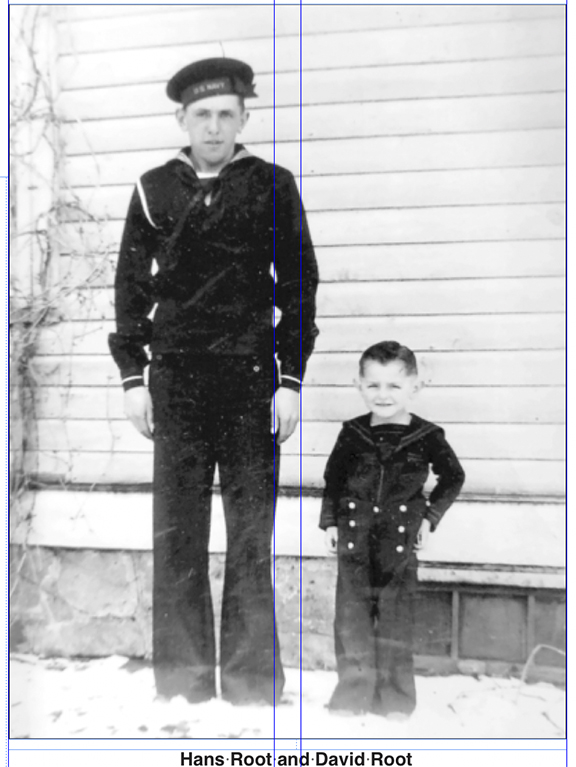

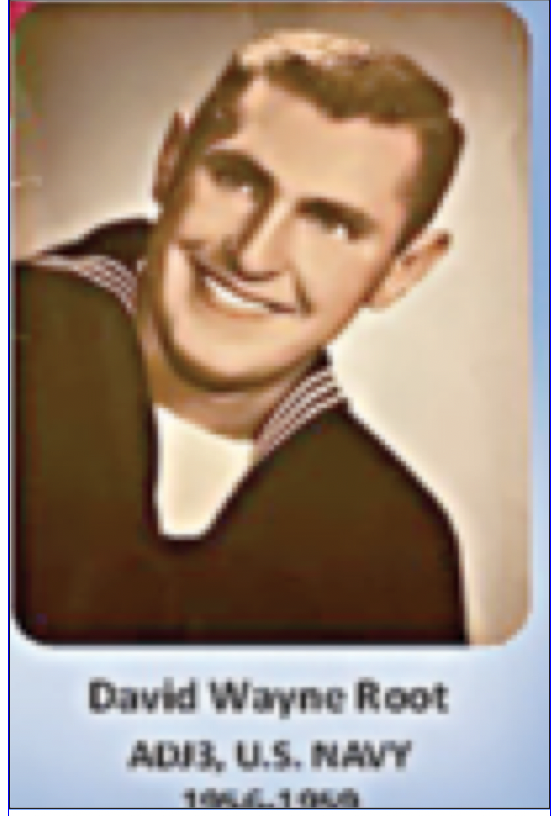

Between January 1942 and December 1972, the Hound Street family of Burchard Bailey Root, (born 1889) and Esther (Gehring) Root (born 1900) was greatly affected by WWII and the conflicts which followed. Of the couple’s seven sons, five served in the US military. Of the two who did not, one had died shortly after birth; the other sacrificed his wishes of fighting in Korea to the responsibility of maintaining the home farm during a time of family crisis. In order of age, the brothers are: Vern Russell Root born in 1921, US Navy WWII; Marvin “Hans” “Tiger” Curtis Root, born 1923, US Navy, WWII, Korea, Vietnam; William “Bill” Burchard Root, born 1927, US Navy WWII, US Army Occupation of Germany and Vietnam War; Donald Jack Root, born and died 1928; Orville “Buck” Keith Root, 1931 farmer; Gene “Buzz” Harlan Root born 1933, US Marines, Korean Conflict; and David Wayne Root born 1938, US Navy 1956 to 1959.

David Root

David Root

Clutching his BB gun on a cold autumn morning in 1945, David Root, age 7, was hiding behind a tree when a fox slipped past. He was near his older brother Hans who was leaning against a tree holding a shotgun. Just home from the war in the Pacific, Hans hadn’t participated in family fox hunts for 4 years. Now here was his chance to get his first fox in years and make a little cash on the pelt. But he didn’t move. He didn’t raise his gun. He just stood there motionless. Huddled in his wool coat, he was fast asleep. There was no way for David to arouse him without alarming the fox, which after a moment of hesitation, slipped back into the brush. Sleeping on a fox hunt was not Hans. Before the war in the Pacific, he had been one of the best hunters and trappers in the New Richland area. After four years of service, he may have been tired and in need of a rest. David, on the other hand, was young, untried, and wishing he had been old enough to carry a real gun.

David’s time would come. First, he would undergo many formative events . He would witness Hans and other brother Bill re-up in the military and serve during the next two wars—Hans back to the Navy where he would see action in Korea, while Bill switched from Navy to Army and was sent to Germany for the reconstruction. After several years of debilitation from a stroke, their father Burchard, the patriarch of the family, would die in 1950—when David was only 11 going on 12. Brokenhearted at the loss, David would also be burdened with helping his older brother Orville “Buck” Root run the farm. All the older boys were gone. And now early in 1951, Gene–the second youngest of the boys–was joining the Marines to fight in Korea. Because Orville and David were the only boys left on the farm, all the field work was left to them: The work was hard. It made him strong. His senior year of high school, he lost the state championship final in wrestling by 1 point to a kid who went to a much larger school at a time when there was only one high school division. During his senior year in high school, David was also co-captain of the football team and all conference though he hardly played due to injury. He was tough and raring to go. When he graduated high school at 17, he followed in four of his older brothers’ footsteps–he joined the Navy.

Being only 17 placed him in the “Kiddie program,” which meant his initial service had to be completed before he turned 21. Four other people from the New Richland graduating class also signed up to join the Navy, among them his best friends Bill Jones and Russell Battenfield. Their naval association lasted through the trials of boot camp at Great Lakes near Chicago. After that they were split up to pursue their separate assignments.

David Wayne Root was slated to become a jet mechanic, but his training process was characterized by the old military adage “hurry up and wait.” First stop was a naval supply station in New Jersey where he would spend 6 months waiting for a slot to open up in Jet Mechanic school. In New Jersey he worked as an assistant to a civilian secretary. To offset the boredom, he took a civilian job setting pins at a bowling alley. In the 1950s setting bowling pins was an old fashioned manual endeavor which called on the pin setter to crawl under the sweeping gate and set each individual pin. One night he injured his leg and it later became infected.

After New Jersey, he was sent to school in Memphis, Tennessee, for four months of classes on jet engine theory. During off time, David often saw Elvis Presley driving around in a pink Cadillac.

Next stop on his training regimen was Norman, Oklahoma, where he would finally get two months of hands-on experience with jet engines. Here he would also suffer his second injury while in the military. After a joke involving shaving cream, a feather, and a sleeping shipmate went awry, David admits to probably laughing the hardest of the offending sailors. He was forced to defend himself. With his wrestling prowess, David easily subdued the enraged sailor. When he figured the guy had calmed down, he let him go. As the retinue of sailors were exiting the barracks, the offended sailor turned around and, from the step below, threw a sucker punch that broke David’s nose.

David’s final injury would come much later and be the result of the cumulative effects of working with jet engines. Now in his 80s, David receives disability from the Navy after an arduous application interview process concluded that his work on jet engines had substantially damaged his hearing, leading to hearing loss of more than 30%. The damage likely occurred during his next assignment in California where he would do what he had ultimately been trained to do--work on fighter jets. He was stationed at Miramar Naval Air Station, Alameda Naval Air Station, and in the deserts of El Centro and near Fallon, Nevada, where the Navy conducted gunnery practice and short takeoffs and landings; the purpose was to train pilots for the rigorous demands of being based on aircraft carriers. Finally, he would do his work aboard the USS Ranger.

Though all the naval jet mechanics worked together, they were each assigned and responsible for two jets. One of David’s jets would crash over the desert after the pilot had ejected safely. The problem had been a manufacturer’s systems snafu that would come to light when another Demon FJ3 crashed soon after.

“By the time we lost two planes we couldn’t use the afterburner,” David clarified. “It took some severe modifications done by McDonald Douglas engineers.”

Though he and the other sailors were often placed on stand by and high alert because of global issues such as the crisis in Lebanon, David’s time in California was not all work and no play. He and his buddy would often hitchhike to Los Angeles on the weekends to chase women and go to clubs. Once, he and a buddy from Florida piqued their fellow sailors' envy when two women showed up at Miramar in a convertible with the intent to take David and his pal to LA for the weekend. On occasion all his sailor buddies tried unsuccessfully to get into Deano’s (Dean Martin's Club). Once while he and a friend were hitchhiking, a convertible pulled over. It was Rock Hudson, who said he only had room for one. Both sailors declined. The famed sexual decadence of Hollywood was everywhere. When approached by gay men near Hollywood and Vine, David would reject them with his classic farm boy humor. “Get way from me,” he would say, “I’m working this side of the street.”

By the time David’s service was up in 1959, he had decided not to re-up. He had already started taking a night class. The day he was discharged from the Navy, he started hitchhiking from San Diego to White Sands, New Mexico, where his brother Bill, now in the army, was stationed. Together, they drove north to Denver to meet their brother Gene “Buzz”, the second youngest boy. Buzz, who had served as a Marine in the Korean War, was working for a road construction company. From Denver, David would hitchhike alone back to Minnesota.

The GI Bill was not in effect at the time, so obtaining a degree and an occupation was a long way off. David married Majel Hintz, my mom, had three kids and moved to Denver to work construction with Buzz. He considered reenlisting when the Vietnam war started, but chose not to because he was already a father to three children. He was working construction at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs when the GI Bill was reinstated. He jumped at the chance, went to college, and obtained a Master’s Degree in Vocational Rehabilitation Counseling. He is the last surviving son of Esther and Burchard Root.

Editorial Note : The girls of the Root clan were no less patriotic than their brothers and bear mentioning here as their names may be scattered throughout the coming articles: Anita (Root) Jewison born 1922 who quit her job as a beautician to work at a factory making radio equipment for the military during WWII; Barbara (Root) Tolzmann, 1925 who was training to be a teacher at the time of WWII; Nona (Root) Smith, January 1929, who married David Smith a sailor in WWII, and whose son George was wounded in Vietnam; Iola "Odie" (Root) Schroeder Borchert December 1929; Thelma (Root) Yess 1934 who married Orville “Ibb” Yess who served in Korea; Opal (Root) Hofius 1935, who married Charles Hofius, US Army Korea. Opal Hofius, her two sons also served in the military, Donnie Hofius and Chad Hofius.